Our Future of Britain initiative sets out a policy agenda for a new era of invention and innovation, based on radical-yet-practical ideas and genuine reforms that embrace the tech revolution. The solutions developed by our experts will transform public services and deliver a greener, healthier, more prosperous UK.

Chapter 1

The United Kingdom (UK) is not on track to meet its decarbonisation targets. The country needs an economic and societal transformation not seen since the Industrial Revolution to maintain its position as a global leader on tackling climate change, to secure low-cost and abundant energy supply, and to reap the economic rewards of the new global clean-technology economy.

While there has been significant progress on reaching legally binding targets set by the independent Climate Change Committee (CCC), the next steps towards net zero will be far more challenging. Still, they will present opportunities to drive economic growth and increase energy security. In the next decade, Britain will need to convert its homes, cars and some industrial processes to run on electricity, decarbonise electricity generation, and build an electricity grid that has enough capacity to handle this increased demand and supply. Britain needs a decade of electrification.

The need to rapidly accelerate the adoption of electric technologies over the next decade to meet net-zero targets has been widely recognised, but to date the UK has not adopted a cohesive, practical plan to deliver the requisite infrastructure and markets. While the United States (US), China and the European Union (EU) race ahead with well-funded and clear delivery plans, the UK’s current policy is not ambitious enough. The government is set to miss its own net-zero targets and fail to attract the investment required to deliver key energy technologies in the process.

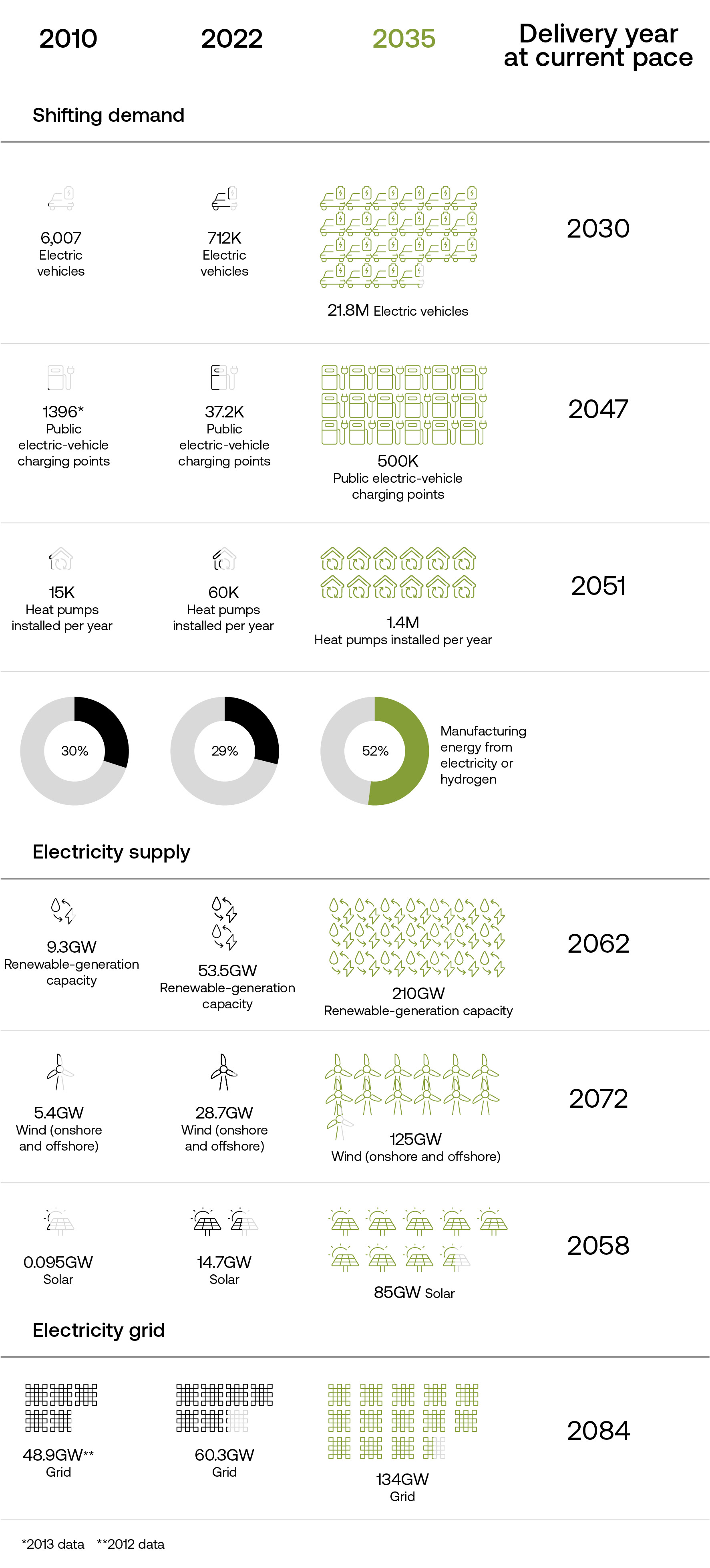

Our analysis shows that on the current trajectory the UK will not deliver enough renewable power to decarbonise the electricity grid until 2062. The government’s goal of installing 600,000 heat pumps per year by 2028 is currently on track to be delivered in 2039. The country will not even have an electricity grid that is fit for purpose until 2084. At the same time, investments and innovative companies are moving elsewhere. The UK is losing out on the potential economic benefit a decade of electrification can deliver.

A decade of electrification could be an engine of growth and opportunity for the UK. Using domestically sourced electricity to power homes, transport and industry will allow the UK to enhance its energy security by reducing its reliance on imported fossil fuels. Estimates suggest that net-zero industries, of which electrification supply chains and services are a main component, could be worth £1 trillion by 2030.[_]

We have designed a four-part policy programme that will allow government and industry to move faster, build faster and advance beyond target-setting to create markets for investment in innovative technologies. This plan will allow government and industry to spur innovation while maintaining energy security, delivering continued growth and prosperity, and protecting the value of personal choice. The government must collaborate with industry to:

Build the underlying infrastructure necessary to supply double the electricity currently available, which the UK will need to meet its net-zero targets.

Attract investment through strategic use of public finance and policy that signals the country’s long-term ambition to decarbonise, which will create favourable conditions for a market of private-capital investment in new technologies.

Boost consumer and business confidence in climate-conscious choices.

Unleash innovation in energy and electrification through a regulatory regime that prioritises investment in efficient, consumer-friendly solutions.

The UK can create a modern, world-leading energy system that delivers cheap and abundant energy for everyone. The country can build an economy fit for the 21st century and reclaim leadership in the global effort to reach net zero. The decade of electrification is an opportunity to create a greener and more prosperous Britain.

Chapter 2

Although significant challenges lie ahead, the UK has already made progress towards reaching its legally binding climate targets. The country has reduced its territorial carbon emissions by 47 per cent compared to 1990 levels.[_] This has been achieved mostly by moving away from coal generation (first to gas, then to renewables), improvements in energy efficiency and offshoring a large proportion of manufacturing activity.

However, the next stage of delivery on the path to net zero will be far more difficult. To meet carbon budgets and cut emissions by 68 per cent by 2030 and 78 per cent by 2035, compared to 1990 levels, the country will need to rapidly move away from fossil fuels. This involves electrifying large parts of the economy while simultaneously decarbonising and expanding the electricity supply. This poses a significant delivery challenge.

Comparing the UK’s progress since 2010 with what it needs to accomplish by 2035 makes it clear that the pace of delivery needs to speed up significantly. Current policies will not be enough for the country to meet its ambitious targets.

Progress in electrification from 2010 to 2022 and targets for 2035

Sources: Digest of UK Energy Statistics (DUKES), National Grid, Office for National Statistics (ONS), CCC

Delivering a decade of electrification is a significant challenge. Currently only 12 per cent of the energy consumed in the economy comes from renewable sources. This means that 88 per cent comes from fossil fuels like oil and gas.[_] The task of moving from a majority fossil-fuel to a majority electric economy can be broken down into three challenges:

shifting energy demand to electric sources

building enough renewable-energy-generation capacity to power the transition

expanding the electricity grid

Challenge 1: Electrifying (Almost) Everything

To meet emissions targets, the UK will need to move away from transport, buildings and industry that run on fossil fuels and electrify most of the economy over the next decade.

Britain is currently progressing well towards its target for electric vehicles (EVs). However, continuing the rapid rise in electric-car sales and moving beyond early adopters to the mainstream will depend on delivering an extensive and high-quality charging infrastructure, which must be in place ahead of need, and a second-hand EV market that consumers can trust. Numbers from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders suggest that the rollout of chargers is not keeping pace with the number of cars on the road, particularly in the North West and the South West.[_] The government’s own EV Energy Taskforce suggested that the country will need 500,000 public EV chargers in 2035 – over 11 times more than the 43,600 public chargers in place now. At the current rate, there will not be 500,000 charge points until 2047.

Electrifying heating, however, is a far more significant challenge that the UK is a long way from meeting. Last year about 60,000 heat pumps were installed across the UK. At this rate, the country will not reach either the CCC’s 2035 balanced-pathway target of installing 1.4 million heat pumps per year before 2051 or the government’s 2035 target of installing 1.9 million per year before 2057. The UK is not even close to being on track for the government’s own target of installing 600,000 heat pumps per year by 2028, which at the current pace will not be achieved until 2039. This target is below the CCC’s trajectory of installing 900,000 heat pumps per year by 2028, which means that the rate of installation may need to increase beyond 1.4 million by 2035 to meet the sixth carbon budget, covering the years 2033 to 2037.

This comes alongside slow progress on improving the insulation of existing homes, which is central to reducing household energy demand, increasing thermal comfort for residents, helping heat pumps to operate at high efficiency and improving a building’s Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating. At the current rate, it will take almost 200 years to achieve the government’s 2035 target of an EPC rating of C across all homes, according to the UK Business Council for Sustainable Development. This is on a scale of A to G, where A is the most efficient.

Progress towards electric-vehicle sales and heat-pump-installation targets

Source: DUKES, CCC, TBI analysis

Electrification is also needed in industry. Studies have shown that 78 per cent of Europe’s industrial-energy demand could be electrified using technologies described as “fully developed and established in industry”.[_] The CCC has set out that 52 per cent of energy used for manufacturing should come from electricity generated directly or indirectly through hydrogen. Currently, about 30 per cent of the energy used in manufacturing comes from electricity. The rest is composed of fossil fuels. The government has previously outlined its intention to reduce emissions by two-thirds by 2035, in part by switching 20 terawatt-hours (TWh) to low-carbon fuels by 2030.[_] Without practical policies the UK will fail to meet this target.

Challenge 2: Powering a Decade of Electrification

The government has committed to decarbonising the electricity supply by 2035. CCC analysis suggests that this will require a renewable-electricity capacity of 170 gigawatts (GW),[_] almost 120GW more than 2022 levels. But looking at progress over the past ten to 15 years, without strategic policy action the UK is likely to miss this deadline.

An electrified economy will require much more electricity than a fossil-fuel economy. At present, fossil fuels comprise about 40 per cent of the UK’s electricity supply.[_] To meet the government’s targets, almost all of the country’s energy must come from clean-power sources, meaning electricity demand is set to double by 2035.

The scale of renewable-energy generation in the UK

Source: DUKES, CCC, TBI analysis

As demonstrated in Figure 3, the UK is behind on renewable-energy delivery. Even in an optimistic scenario the country will be five years behind the government’s offshore-wind target of 50GW by 2030. Delivery of onshore wind has declined since 2017 because of the de facto ban on onshore developments. At the current rate it will take 50 years to hit government targets for solar energy – or 151 years based on the capacity added in 2022. Researchers from the University of Liverpool[_] have estimated that an average monthly installation rate of 361 megawatt peak (MWp)[_] would be required to meet the government’s targets. This would require a sustained level of installation matching the previous peak, which was reached during a period of strong incentives for consumers to install solar power in their homes.

Looking at the pipeline of projects, the pace of energy-generation delivery could be accelerated. There are currently 100GW of offshore wind registered at different stages of the pipeline.[_] Currently it can take about four years for an offshore wind farm to gain a development consent order and a total of 13 years for construction. To maximise the potential of the projects in the pipeline, the UK needs an expedited planning process, as outlined in our paper Building the Future of Britain so projects of national importance receive consent and so the pace of securing grid connections for new clean-energy inputs increases. This process takes 50 months on average but can take up to 15 years.[_]

A fully decarbonised electricity system will also require infrastructure to store energy to manage the peaks and troughs of renewable-energy supply and demand throughout the day and year – for instance, storing solar power collected during the summer months for usage in the winter when energy demand is higher and daylight hours are fewer. Storing energy efficiently will require a range of technologies that are currently at different levels of maturity. The CCC has outlined that Britain will need 17GW of dispatchable low-carbon energy and 11GW of grid storage by 2035 in their most likely scenario. The exact composition of this storage and dispatch system will depend on the technological solutions available.

For shorter-term storage, grid-scale lithium-ion and future battery technologies will be a core part of the solution. There is currently a strong pipeline of battery projects waiting to come online,[_] but it is crucial that these are in the right locations and that they connect to the grid in a timely manner. Solutions at the home level, including domestic-scale batteries and using EVs as flexible batteries, may also form part of the future of storage.

Longer-term storage solutions to replace current gas generation is a more significant challenge. This function is likely to be filled by either hydrogen generation or gas generation with carbon capture. By 2030, the government aims to capture and store 20 to 30 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon per year and to produce 10GW of hydrogen energy, at least half of which is to be green. The energy bill is an important step towards making this happen, but it is unlikely the UK will have sufficient capacity to deliver this type of flexibility at scale and low cost at the current pace of delivery.

The government has also committed to building at least 18GW in interconnectors – cables that link the energy systems of different countries – by 2030. This could help introduce further flexibility into the energy system, transporting energy between countries to help balance demand and supply, and will eventually be key for the UK’s ambition to become a net exporter. The UK is already well on its way to integrating with Europe, with 7.8GW of interconnector capacity due to be online by 2024. [_] There are also new innovative projects in the pipeline such as LionLink and Xlinks, a UK-Morocco power project.

Challenge 3: Expanding the Grid

The grid is a core enabler of the decade of electrification, and it needs to be available ahead of need rather than blocking progress. The CCC has asserted that to deliver clean power, the UK needs to double the size of the transmission grid by 2035,[_] which will require building 65.8GW of grid between 2025 and 2035. This stands in contrast to the 11.35GW of grid capacity built in the UK from 2012 to 2021. If progress continues at the pace of the past decade, the grid will not be large enough to meet renewable-energy targets until 2084; if it continues at the average pace of the past five years, it won’t meet demand until 2132.

The capacity of the UK’s electricity-transmission grid

Source: DUKES, CCC, TBI analysis

A similar upgrade is expected to be needed for the electricity-distribution network. Currently, outdated regulations are causing delays in securing grid connections and holding back installations of EV chargers and heat pumps. These delays could also impact infrastructure such as housing, data centres or even new industry.

The scale of investment needed at the distribution and transmission levels will depend on the degree to which the UK is able to make the most of flexible solutions and optimise the placement of generation in relation to demand. A more strategic approach is needed to ensure Britain builds an energy system and electricity network that minimises consumer costs and disruption while maximising the efficiency of the UK’s infrastructure.

Chapter 3

The UK needs to radically overhaul its approach to deliver a decade of electrification. The government needs to implement an ambitious yet practical delivery plan that is tailored to the scale of change required, deploying public funding and attracting private capital by giving industry and the public the confidence to invest.

The state needs to act with urgency, but plans cannot be rash. The government must carefully consider what conditions are needed for delivery and ensure public buy-in and understanding of new regulations. Forthcoming bans on new internal-combustion-engine cars and vans from 2030, new oil boilers from 2026 and new gas boilers from 2035 are not backed by policies to ensure it is easy, desirable and affordable for consumers to switch to alternatives. Without the latter, the government risks imposing significant hardship, losing support and damaging the public’s belief in its ability to deliver. A decade of electrification can only be achieved through cohesive and practical delivery plans.

As set out in our recent paper A New National Purpose: Innovation Can Power the Future of Britain, the UK needs to become a more strategic state that thinks radically about how to move at a faster pace, take greater risks and build long-term sustainable policy. The strategic state intervenes to create the underlying markets and structures required to deliver a self-sustaining transition and only uses blunt tools such as banning gas boilers or stopping oil and gas exploration when the conditions are in place to deliver an affordable and secure transition. Only through this kind of action can the UK deliver on its net-zero targets in a sustainable way and reap the economic benefits of the clean-technology revolution.

The strategic state should employ four key approaches to designing policy that supports bold steps towards net zero using electrification. First, building the underlying infrastructure that is needed, at scale and at pace. Second, creating favourable conditions for investment to crowd in private-sector funding. Third, acting to give consumers and businesses the confidence they need to transition from fossil fuels to electricity. And finally, establishing a regulatory system that unleashes innovation in energy and electrification.

Build More, Faster

The decade of electrification requires a large amount of new, modern infrastructure. Britain will need to build at a speed not seen since the post-war period. From its electricity grid to wind farms to EV-charging infrastructure, the country needs a regulatory and policy environment that allows fast delivery of infrastructure where people need it.

The government should:

Reform the planning system to enable quick delivery of infrastructure, ensuring that decisions on nationally significant infrastructure projects (NSIPs) are made within six months and that projects of national importance receive consent. The government also needs to deliver reform beyond NSIPs, including strengthening land-use rights for distribution-grid operators and improving the efficiency and capability of local authorities in handling planning permission requests for EV chargers and heat-pump installations.

Reform the Ofgem regulatory regime that currently puts short-term cost savings for customers ahead of the long-term benefits of building out the grid for the future. Delivery of infrastructure for a decade of electrification should be the core of what Ofgem and the National Grid do. Maintaining the grid is no longer enough; it must be expanded. Reform should involve allowing the National Grid to assess and prioritise grid-connection applicants and the renewable projects in the queue rather than addressing them on a first-come-first-served basis. It will also be crucial that the new, independent Future System Operator (FSO)[_] is established with a clear remit to plan the future grid and draw together all areas of government policy that demand grid capacity. The FSO needs to urgently make strategic decisions regarding storage investments to ensure that renewables development is accompanied by appropriate storage solutions in the right places. Consideration should also be given to deregulating transmission-grid provision and allowing companies to build their own transmission lines, as Octopus Energy CEO Greg Jackson recently suggested.

Digitise the grid and improve grid-management techniques to minimise the need for further building and maximise existing assets at the home, building, local and national levels. Furthermore, using digital-twin technology would provide a model for simulating supply and demand scenarios and opportunities to maximise efficiency. The government should also allow exploration of how the latest grid technology could minimise on-land infrastructure requirements.

Improve interconnection with Europe and beyond to strengthen the grid with additional sources of electricity supply. Building upon the European energy islands, the government could develop an integrated grid in the North Sea that can provide flexibility and capacity for the UK when it is needed. This will require careful work both in a UK context and with the EU to agree relevant regulatory models. In addition to this, government policy should encourage and support long-distance interconnectors such as the one with Morocco, which could provide similar benefits.

Attract Investment

Delivering a decade of electrification will require significant capital. A strategic state[_] needs to use public spending and its own balance sheet strategically to attract private capital, create self-sustaining markets for delivery and minimise risk. As we wrote in Copy, Compete, Collaborate, the UK’s net-zero policy needs to be predictable and long-term to give industry the confidence to invest.

To create attractive investment positions the government should:

Introduce long-term funding schemes with clear delivery timescales to create market certainty for green industries such as the heat-pump industry. Such schemes could include incentives to improve the energy efficiency of social housing.

Use public funding strategically as risk-sharing capital or introduce guarantee schemes for new technologies and business models to de-risk investments for lenders and investors and help bring technologies and business models to maturity and scale. This could include strategic support from a bank that supplies financing for infrastructure, such as the UK Infrastructure Bank.[_] The state should also make the pension capital-gains tax exemption apply only to funds that allocate 25 per cent to UK assets, to incentivise pension funds to support Britain’s burgeoning clean-energy sector.

Improve net-zero related measurements and classifications to help financial institutions internalise climate risk, channel investment to the right types of projects and avoid “greenwashing”. This should include building upon the Transition Plan Taskforce and the work to implement mandatory disclosure and standardisation of transition plans, which would allow financial institutions to channel investment towards companies that are taking the most proactive steps to manage climate-related risk. The government should also develop a taxonomy for green and transition capital in a way that considers cross-border investing and seeks routes to international harmonisation where possible. More widely, the public and private sectors should collaborate to improve financial institutions’ access to climate-related data throughout the economy. The Perseus project[_] is an example of how this can be done.

Develop agreements to build secure supply chains and include national strategies for key sectors. For example, agreeing ten- to 15-year framework agreements for grid suppliers to encourage investment in their capability, supply chains and workforce. It also needs to include a comprehensive strategy for critical minerals and other core strategic global supply chains, including specific agreements with mineral-rich countries and key players like the US and EU.

Ensure the tax system encourages investment in clean technologies over the longer term. This should include shifting to permanent full expensing for investment in grid infrastructure and renewables. It should also include measures such as introducing an energy-efficiency-adjusted stamp-duty land tax as suggested by UK Finance,[_] to encourage energy-efficiency retrofit and heat-pump installations at the point of purchase.

Boost Consumer and Business Confidence

The decade of electrification will impact consumers and businesses throughout the UK, but the market is not currently set up to make climate-conscious choices simple and straightforward. Britain needs policies that empower consumers and give them the confidence to invest in new technologies.

Policy design should start from the perspective of the consumer, and it should consider how best to use data and information to provide an enhanced service.

The government should take steps to:

Rebalance the cost of gas and electricity by shifting the environmental levies away from electricity, recognising that electricity is lower carbon and cheaper than gas. These levies should be moved to general taxation to shift the incentives away from gas towards electricity appliances for consumers.

Give local authorities enhanced powers and resources in net-zero delivery. Determining where to place charge points or what homes are best suited for heat pumps, as well as guiding consumers through that journey, are fundamentally local issues that require local leadership and planning. To plan and consult effectively, local authorities need additional resources.

Government could use artificial intelligence (AI) and data to provide more personalised advice and guidance to consumers and businesses on their net-zero journeys, as suggested by the Centre for Net Zero.[_] In the home, this needs to include reform of EPC ratings so that they provide helpful information about their properties and practical advice, as we explored in our paper Three Birds, One Stone.

Incentivise consumers to invest in green technologies through schemes such as feed-in tariffs and scrappage schemes. For homes, we have outlined what a new financial offer could look like in our paper Three Birds, One Stone.

Establish clear standards for the second-hand EV market in collaboration with the automotive industry.This should involve creating an easy-to-understand consumer standard for testing and reporting the health of the electric drivetrain system and battery of second-hand EVs. There should also be a fully funded training programme for mechanics at garages and dealerships to certify their ability to test, modify and repair the electric drivetrain system and batteries of EVs.

Ensure the consumer-oriented industries are set up to guide customers through the transition to green technologies. Through clear signals, market reform and engagement, empower key players such as energy retailers and mortgage lenders to take a more active role in guiding and supporting consumers. For instance, through flexibility trials, Octopus consumer energy made it easy for consumers to save energy, thereby shifting 2.92GWh of energy from peak periods.[_]

Unleash Innovation

While the UK already has many of the core technologies needed for a decade of electrification, innovation in technology and services remains essential to efficient, consumer-friendly solutions. Rapid innovation in areas such as AI and electrification is happening across society, policy must harnesses this potential rather than lagging innovation.

The UK can reform its regulatory regime to create incentives for innovation that are aligned with electrification by shifting the focus from outputs to outcomes, with government setting the direction and industry working with consumers on how to achieve it.

Government and industry leaders could:

Conduct reform of the wholesale energy market to align market design with the decentralised physics of emerging technologies and a more electrified, flexible demand side, for example by introducing local marginal pricing. As suggested by the Energy Systems Catapult,[_] this could reinforce the UK’s position as a leader in demand-side innovation on storage, flexibility and consumer products and usher in demand-side responses and virtual power-plant solutions. The retail market also needs to be reoriented away from its current low-risk, cost-effectiveness-oriented approach to allow energy retailers to offer more innovative packages to consumers, including energy-management technology and heat pumps.

Increase R&D investment in core green technologies. This should include working with international partners. As proposed in A New National Purpose, this should become a key national benchmark.

Treat data as a competitive asset that can be used to drive down the cost of delivery and build high-value data sets that can be used for innovation. For instance, collecting data through additional “Living Lab” schemes – such as the Siemens collaboration with the University of Birmingham or the Energy Systems Catapult’s network of connected homes – could help test innovative technologies. These models could be implemented in similar settings or even whole towns.

Chapter 4

The decade of electrification is an opportunity to create a greener and more prosperous Britain. By implementing our policy plan, focused on practical steps towards targeted outcomes, the UK can create an economy fit for the 21st century and a modern, world-leading energy system that delivers cheap and abundant energy for everyone.

Green technology is an area in which the UK has traditionally been an early mover and there are opportunities to stake a claim in the future global clean-technology economy. Adopting the policy changes proposed could unleash UK leadership in specific areas of clean tech. For instance, the UK could build upon its strong experience in software and sensors to become a leader in flexibility and grid-management solutions, or build upon its strong research and innovation base to become a leader in new technologies like tidal or floating offshore wind.

Ultimately, to tackle climate change we need a global decade of electrification. The policies and institutions developed in Britain can become a blueprint for the rest of the world to follow and an anchor of UK economic growth and prosperity.