Chapter 1

Although the culinary and linguistic differences between North and South India are widely known outside the country, less well understood abroad are the differences in how the two groupings of Indian states have fared on development. A comparison of Tamil Nadu, a southern state, and Uttar Pradesh, a northern state, is indicative of broader regional trends. In 1960-61, these two states were not so different across a number of measures related to development, albeit with Tamil Nadu achieving a generally higher performance. For instance, at that time, Tamil Nadu had a per capita income 51% higher than that of Uttar Pradesh—5,053 as compared to 3,338 Indian rupees.[_] This gap, however, narrowed to 39% by the early 1980s. The two states were even closer together when it came to poverty: from the early 1970s (and probably before) to the late 1980s, Tamil Nadu’s poverty rate was equal to or higher than that of Uttar Pradesh. In fact, in 1960, the rural poverty rate in Tamil Nadu checked in at just below 70%, much higher than Uttar Pradesh’s rate of 48%.

Decades later, we see a much different situation. By 2005, Tamil Nadu’s per capita income outpaced Uttar Pradesh’s by 128 percent—a gap more than twice as big as it was in the early 1960s. And in 2009-10, Tamil Nadu’s rural poverty rate dropped to nearly half that of Uttar Pradesh (21.2% vs. 39.4%), and its urban poverty rate was less than half of Uttar Pradesh’s (12.8% vs. 31.7%).

Today, Tamil Nadu is India’s second-largest economy despite being only its sixth most populous state, and among India’s 12 largest states, Tamil Nadu has the third-highest GDP per capita.[_] Located at the southernmost tip of the subcontinent with a population of more than 70 million, it is India’s most urbanised state and one of its most industrialised, with a strong manufacturing base and a large services sector. At the same time, it ranks second on the Human Development Index among India’s 13 largest states.[_] In other words, the state has achieved high growth rates and economic transformation in combination with significant progress on social outcomes, which has been key for enabling broad swathes of the state’s population to share in its growth.

How did Tamil Nadu do this? The state’s development path illuminates some key points regarding how governments can effectively promote inclusive development. Underlying the policies and investments that the Tamil Nadu state government has pursued are:

An inclusive vision traced out by widely popular Tamil cultural figures turned political leaders, such as former chief ministers (the top executive post at the state level) M. Karunanidhi and M.G. Ramachandran (widely known by his initials MGR), for whom social justice and uplifting disadvantaged groups were central concerns

Policy consistency and commitment of the state’s political leadership to industrial development, which cut across the administrations of Karunanidhi, MGR and their successor Jayalalithaa, as well as the predictability that this created over time for investors—despite power alternating between the state’s two primary parties on a regular basis

The effectiveness of the bureaucracy in policy implementation, due to the recruitment of socioeconomically diverse cadres who were attuned to local challenges; the ideological ties between bureaucrats and the regional political parties (and the competitive pressures to deliver that this created); and the establishment of specialised agencies, such as the Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation (TIDCO) and the State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu (SIPCOT), to drive delivery of the state’s economic vision.

The state’s competitive, clientelist political system and history of towering political leaders are also common features of politics in many African countries. As a result, Tamil Nadu’s experience in channelling this system towards inclusive development holds important lessons about governance that can be instructive for African countries.

Chapter 2

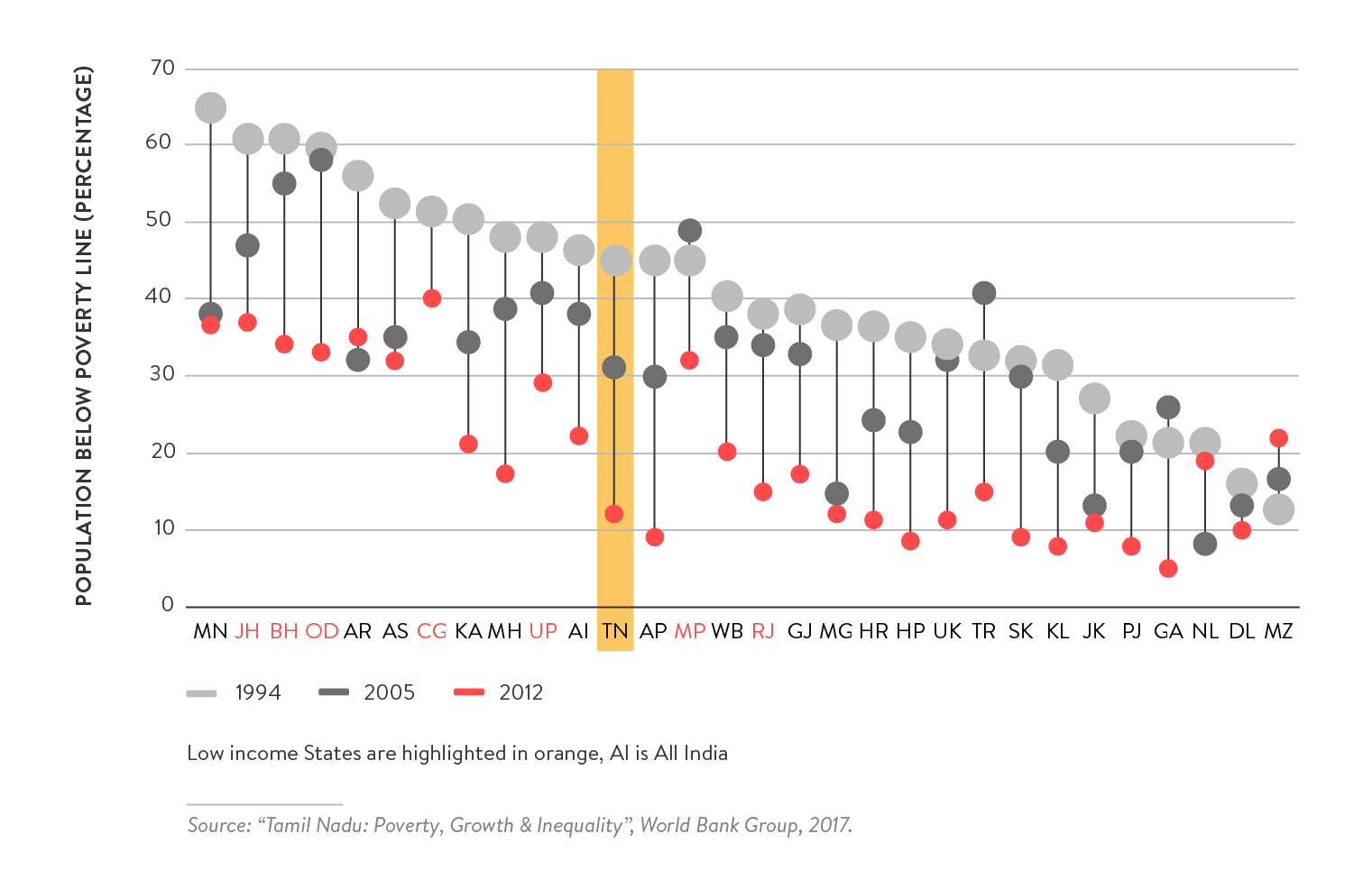

Tamil Nadu has been one of India’s best-performing states when it comes to inclusive development. Since 1994, poverty has declined steadily in the state, resulting in Tamil Nadu having lower levels of poverty than most other states in India. This trend has played out in both rural and urban areas of Tamil Nadu, the former seeing a 35-percentage point reduction in poverty between 1994 and 2012 and the latter seeing a 27-percentage point reduction during the same period.[_]

Population below poverty line across Indian states, 1994-2012

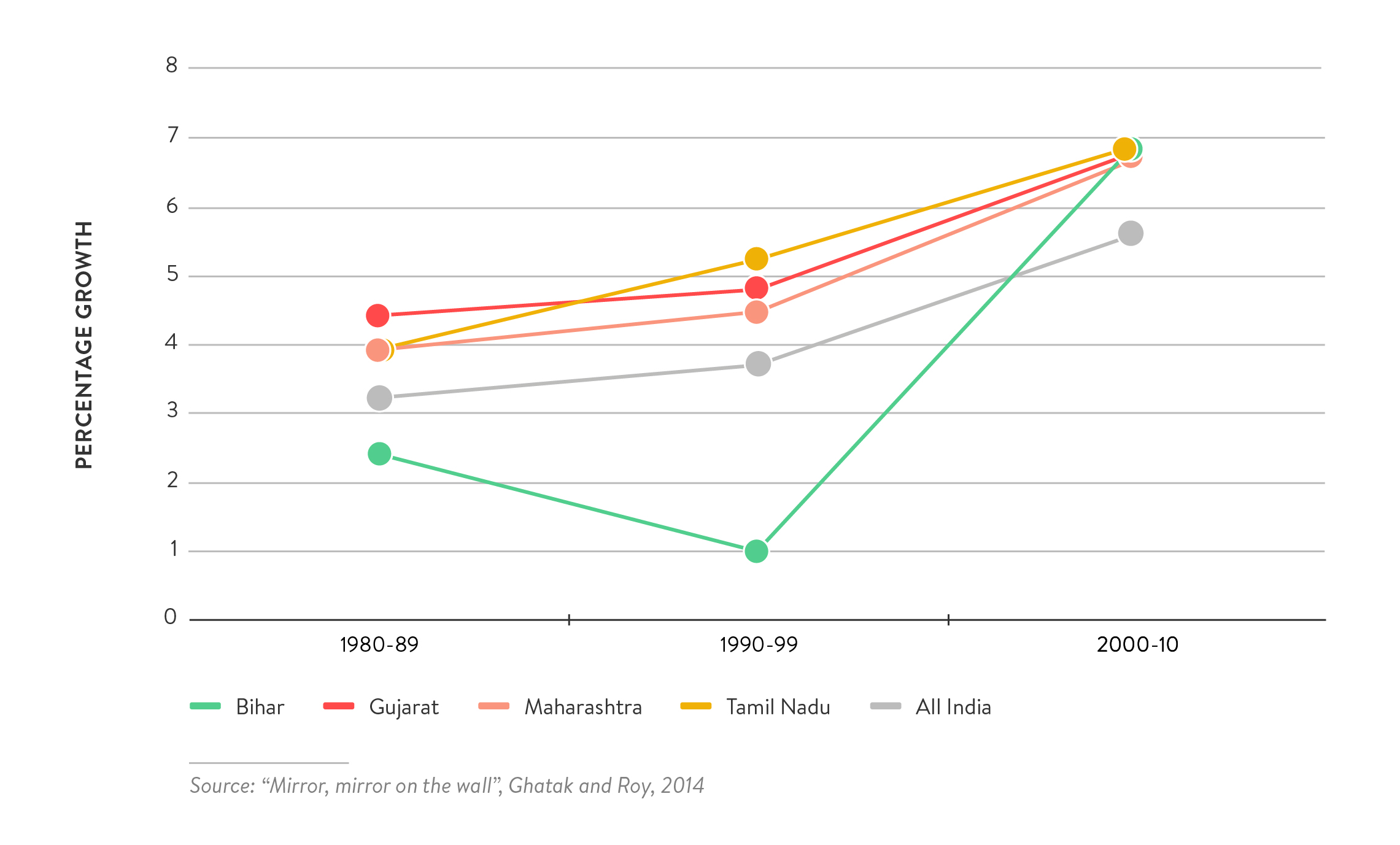

Rapid economic growth over the past several decades has played a major role in the state’s poverty reduction story. From 1991 to 2012, Tamil Nadu averaged 7% growth in GDP and approximately 6% growth in GDP per capita[_]—both clocking in above the all-India average.[_]

Average annual growth rate of per capita income in selected Indian states, by decade

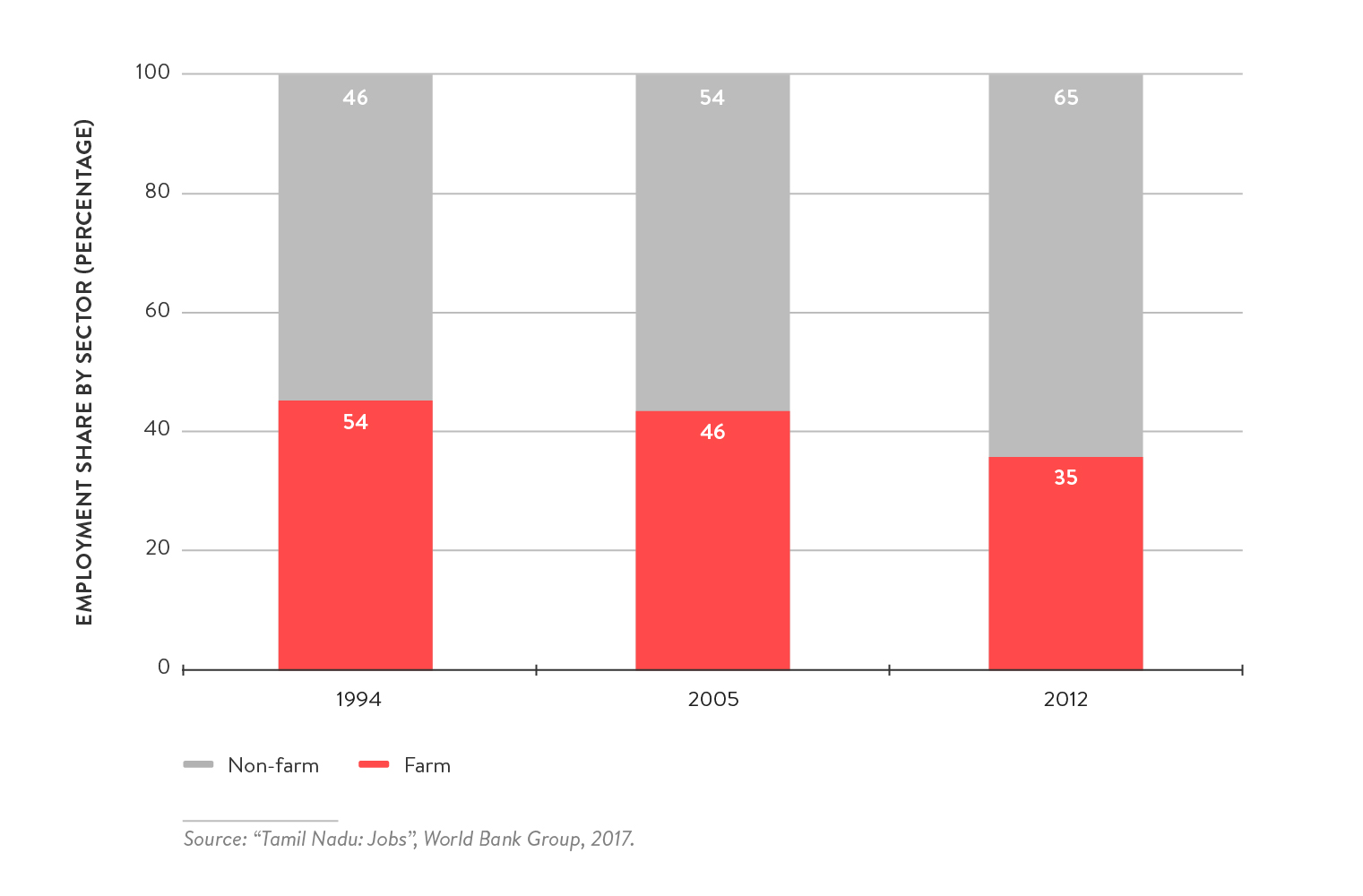

Importantly, economic transformation has underpinned the state’s growth, as people in Tamil Nadu have moved off the farm and into other types of work over time. The state’s non-farm employment share in 2012 ranked fifth among all Indian states.

Employment share by sector in Tamil Nadu, 1994-2012

Services have led the way in terms of contributing to growth and employment, but industry has also played a critical role—accounting for approximately 30% of Tamil Nadu’s growth between 1991 and 2012.[_] The state ranks first among all Indian states in terms of number of factories and industrial workers, and has a diversified manufacturing sector. It is among the leading states in automobiles, components, textiles and garments, leather products, pharmaceuticals and other industries.[_] Major automobile manufacturers, such as Hyundai, Ford, Renault and BMW, have had production facilities in and around Chennai (the capital of Tamil Nadu) for years, and the Tiruppur-Coimbatore-Salem corridor has been dubbed the “Manchester of South India” due to its large cluster of textile firms.

This economic success has coincided with substantial progress on human development. Infant mortality has declined substantially and rates are now among the lowest in India. Malnutrition is also among the lowest in the country, and is below the national average for all income groups.[_] Across a range of health indicators, Tamil Nadu stacks up well against other high-growth, high-income states, such as Gujarat.

Table 4: Basic Health Indicators in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, 2005-06

On education, children in Tamil Nadu are staying in school longer, and the share of adults with secondary schooling is above the national average. In terms of educational attainment across socioeconomic groups, Tamil Nadu again compares favourably with Gujarat.[_]

To be clear, Tamil Nadu still has much room for improvement: non-farm job growth has been slow in recent years, and is not keeping up with the expansion of the working-age population; women have dropped out of the labour force (mirroring a countrywide trend); open defecation remains commonplace among low-income households; and learning outcomes in primary school are no better than the all-India average. Nonetheless, the state’s significant economic and social progress both during and after economic liberalisation in 1991 should not be brushed off, as its experience demonstrates what can be achieved when political leadership and governance set out and follow through on a strong, inclusive development agenda.

Chapter 3

Tamil Nadu has successfully combined a coherent industrial policy with social welfare programmes, which has generated a virtuous cycle of development. Industrialisation has provided the resources to invest in social policies, and these social policies have bolstered the health, productivity and skill base of the state’s population.[_] Higher skills among workers, in turn, have allowed the state to move into more complex economic activities, diversify its economy and thus sustain growth.

Industrial policy

Tamil Nadu’s industrial policy has focused on a few key elements. First, the state has invested in infrastructure—upgrading road, rail and port networks—to enhance connectivity between its hinterland, industrial clusters and urban markets.[_] For instance, major ports, such as Chennai, were essential in making the state an attractive location for export industries. Investments in communications infrastructure were also prioritised to enhance connectivity, enabling Tamil Nadu to become one of India’s major IT centres. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the government invested heavily in boosting the state’s electricity generation capacity, a critical input for manufacturing. These investments created suitable background conditions for foreign manufacturers—ranging from Standard Motors in the 1950s to Hyundai and Ford in the 1990s—and domestic business houses—such as the TVS Group, Rane and Amalgamations Group—alike to set up shop and to grow.[_]

Second, the state government emphasised the spatial dimension of industrial development, by promoting industrial parks and clustering. Industrial estates have been a part of Tamil Nadu’s economic landscape since India’s independence in 1947. The accession to power of Karunanidhi and his regional party, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), in the late 1960s reinforced this trend by leveraging new state agencies—and capable Cabinet members, such as the Minister of Industry S. Madhavan—to accelerate industrial development. The Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation (TIDCO), set up in 1965 by the previous Congress Party-led government, obtained many industrial licences and regularly partnered with the private sector to establish new industrial activities in the state, including various IT parks in the 1990s.[_] The State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu (SIPCOT) was established in 1971, and, through aggressive land acquisition, created land banks that enabled foreign investors to obtain land in a more streamlined fashion. These were used to successfully develop many industrial projects and complexes.[_] In particular, industrial clusters and Special Economic Zones (SEZs) have been set up in specific sectors, including in footwear, engineering products, automobiles and IT. Consequently, Tamil Nadu now has the most SEZs in the country and is among India’s highest recipients of FDI.[_] Another result of this spatial focus is that Tamil Nadu’s industrial development is spread out across the state (more so than in most other Indian states), and is diversified across a number of sectors. This has allowed both domestic SMEs and foreign investors to contribute to technological upgrading and the expansion of export capabilities.[_]

Third, the state government pursued complementary policy measures prior to India’s liberalisation in 1991 that readied Tamil Nadu to grasp new opportunities as they arose in post-liberalisation India.[_] For instance, MGR opened new avenues for education, particularly geared towards industry. His administration expanded lower-level technical education by setting up a variety of industrial training institutes and polytechnic colleges all over the state—thereby laying the foundation for Tamil Nadu’s successful automobile industry.[_] Starting in the 1980s, he also allowed private groups to establish engineering and medical colleges. While this was a means to distribute patronage (e.g. land below market-value rates, privileged access to a lucrative business opportunity) in exchange for political support, it helped to create a pool of human capital that has effectively served the state’s fast-growing IT sector since the 1990s.[_] Forward-thinking policymaking in the state has continued long after liberalisation—for example, on the contentious issue of land acquisition, where Tamil Nadu amended the process at the state level in 2015 to make it less time-consuming while other states have yet to take such steps.[_]

Social Policies

While other Indian states have pursued similar industrial policies, Tamil Nadu stands out in its parallel focus on social welfare policies, in the areas of public education, social security and healthcare. In addition to technical education, MGR vastly increased the educational quota for disadvantaged communities, from 30% to 69%.[_]Successive governments have strongly supported public education, with concerted efforts aimed at expanding free education and developing a large network of schools and universities.[_] Since the 1970s, various initiatives have been designed to encourage school participation, including the provision of free uniforms, textbooks and laptops, as well as cash incentives to reduce dropout rates. Among these, MGR’s universalisation of the existing midday meal scheme is still widely seen as one of the state’s most noteworthy accomplishments.[_] As a result, Tamil Nadu today has universal primary school attendance, and the highest gross enrolment in higher education in India.[_] These advances have played a crucial role in equipping Tamil Nadu with an educated and technically skilled workforce, making it an attractive state for investment.

Case Study

Midday Meal Scheme (MMS)

The launch of the universal midday meal scheme (MMS) in 1982 is widely seen as a pioneering idea that had a major impact on health and education outcomes in Tamil Nadu. While similar initiatives had been in place since independence, it was MGR, Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu from 1977 to 1987 and leader of the All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (an offshoot of the DMK party), who universalised the idea. It initially served primary schoolchildren in rural areas, and within a few years, all children up to the age of 15 were entitled to a nutritious meal each day in school.[_] At the time of its implementation, the scheme was widely derided by economists as a “populist” programme and a waste of resources.

However, World Bank appraisals have shown that the MMS has curbed malnutrition, reduced infant mortality and lowered birth rates.[_] It has also driven school enrolment rates and led to greater classroom participation. In fact, various studies have found a dramatic positive effect on learning achievements, making the school meal programme a highly cost-effective way to improve skills among future workers. The extent of the MMS’s success can be seen in the fact that the central government adopted the Tamil Nadu model as a template for its own national scheme 20 years later.[_]

In the provision of essential public services, Tamil Nadu follows a universalistic principle, making services as broadly available as possible.[_] This approach has several advantages. Households below the poverty line can be difficult to identify, both conceptually and practically, meaning that targeting public services can lead to substantial exclusion errors. Moreover, when everyone has a stake in the system, its likelihood of working greatly increases. Otherwise, it is often the case that “services for the poor will always be poor services”. India’s public distribution system (PDS), designed to provide households with a minimum quota of subsidised food, is a case in point. From the late 1990s, many states targeted the PDS towards poor households, though Tamil Nadu continued with a universal approach. This is widely acknowledged as one of the primary reasons why Tamil Nadu is one of the states with the fewest leakages of funds in its PDS system. As a result, it has reduced the poverty gap in the state by up to 60%.[_] The experience of Gujarat, another high-growth state, contrasts sharply with this: leakages are as high as 63% and half of the state’s poorest people do not receive any subsidies due to poor coverage.[_]

A similar story can be told regarding healthcare. Unlike most of India’s large states, Tamil Nadu has a clear commitment to widespread access and affordability in healthcare. From the late 1980s, significant investments have transformed the state’s health infrastructure. Initiatives that were launched by the central government were vigorously implemented, such as the large-scale expansion of primary health centres.[_] Moreover, the state has launched its own schemes to complement these, such as the provision of around-the-clock services to improve women’s access to obstetric care or decentralised immunisation programmes. Overall, health outcomes have been transformed in Tamil Nadu. Today, it has the country’s second-lowest infant mortality rate and has achieved a 70% reduction in maternal mortality in the nearly 30 years since liberalisation, an area in which India as a whole is doing poorly.[_] It achieved the Millennium Development Goals far ahead of most states and is well on the way to achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.[_] This focus on healthcare has not only protected public health, but also helped to build the state’s developmental infrastructure, aiding rapid industrialisation. This is illustrated by the fact that areas like Hosur, which have long suffered from endemic plague and cholera, are now seeking to develop as industrial zones.[_]

Chapter 4

Tamil Nadu’s state government has had a major influence on the state’s development trajectory. It has taken an open stance towards investment while simultaneously pursuing policies to ensure that broad swathes of the population could benefit; maintained policy consistency and commitment to industrialisation across changes in political leadership; and built up a bureaucracy that could implement its economic and social policies effectively. As many African countries are also seeking to achieve inclusive economic transformation, they can draw lessons about political leadership and governance from the Tamil Nadu experience.

Forward-thinking leadership married to social development

The political climate in Tamil Nadu has long been influenced by ideas of social justice. Dravidian social movements, representative of the indigenous ethnolinguistic group in Tamil Nadu, have historically been a key player in this regard. These movements, dating to the early 1900s, demanded social reforms and public benefits, particularly for disadvantaged (i.e. lower-caste) groups in society. The role that they have played not only in putting legitimate demands on the state government, but also in birthing the DMK and its offshoot the AIADMK, is frequently cited as a major pillar of the Tamil Nadu model.[_]

In response, Tamil Nadu’s political leadership was forward-thinking in pursuing an inclusive development agenda, particularly in the decades following India’s independence. Both the DMK and AIADMK not only responded to popular mobilisation and public pressure but, in many cases, they were at the forefront of it. Karunanidhi’s predecessor as Chief Minister and at the helm of the DMK, C.M. Annadurai (known as Anna, or “big brother” in Tamil), used theatre and cinema to advocate for anti-nationalist, anti-casteist and other progressive ideas, as he understood that focusing on uplifting disadvantaged groups was a key to progress.[_] Karunanidhi, a lauded screenwriter in Tamil cinema as well as a novelist, political commentator and orator, entered politics not only on the back of his popularity in these domains but also through his direct involvement in local political protests. His time as Chief Minister in the 1960s and 1970s saw a continued focus on the disadvantaged; he made education free, subsidised power and took various other measures aimed at reducing discrimination and supporting the welfare of marginalised groups.[_]

His supporter turned political rival MGR was a Tamil film star, and around this time starred in a number of films that promised that the state government would take care of the poor.[_] Indeed, MGR himself insisted on the MMS in the face of opposition, as he saw it as crucial to prevent hunger and improve learning. His leadership skills were critical in maintaining political support for the scheme and raising funding through tax increases.[_] Similarly, the state’s preventive approach to healthcare relied on a long-term perspective on the part of state leadership, particularly in the face of political pressures to “fight visible fires” that were more immediate.[_] Broadly speaking, social welfare policies in Tamil Nadu were designed to invest in the common man—with the recognition that these investments would drive further growth.

The inclusive ideals of these political leaders have also been reflected in Tamil Nadu’s industrial schemes, particularly regarding land acquisition. The state’s approach includes offering generous compensation packages to the dispossessed, employment and training opportunities, and land redistribution. In other words, “land acquisition in Tamil Nadu is accomplished more through consent than coercion”.[_] Tamil Nadu’s experience contrasts sharply with that of other states, as the establishment of SEZs in the state has encountered no systematic resistance or major confrontation.[_]

Commitment to industrialisation and policy consistency

Since the 1960s, Tamil Nadu’s main political parties have been politically committed to industrialisation. State agencies such as TIDCO and SIPCOT were set up to advance industrial development (see below). From Karunanidhi on through Jayalalithaa, successive chief ministers provided strong political support, in terms of funding and in backing contentious actions such as land acquisition.[_] This political support, in turn, enabled consistent goal-setting at the highest levels of government. With a clear direction from the top, the state bureaucracy was then given space to figure out how to deliver on the industrial development agenda.[_]

Political commitment to industrialisation in Tamil Nadu manifested in at least two important ways. First, political leaders such as Jayalalithaa and their top bureaucrats made hands-on, tailored efforts to attract specific companies and sectors. The automotive industry during the mid-1990s is a notable example. Despite Maharashtra’s existing strengths in the sector, Ford decided to set up its first factory in India in Chennai in 1995. In addition to the facilitation role that the bureaucracy played, Jayalalithaa herself was instrumental in bringing the investment to the state. She made a sizeable chunk of land available to Ford to set up its plant, and offered incentives related to infrastructure, sales and output tax exemptions, and capital and power subsidies.[_] It was also rumoured that Jayalalithaa spoke to senior officials in the US government to encourage them to persuade Ford to invest in Tamil Nadu.[_] Ford’s entry played a catalytic role in developing the sector: Hyundai soon followed Ford’s lead in investing in Tamil Nadu, and the Hyundai plant near Chennai is now the company’s global export base for small cars.[_] The snowball effect has carried on even in recent years, as Jayalalithaa’s most recent administration signed MoUs in 2012 with five global automobile manufacturers, including Daimler, Nissan and Yamaha.[_] Today, Tamil Nadu is one of the top automobile hubs in the world, with a world-class ecosystem centred around Chennai, the “Detroit of India”.[_]

Another example is the IT sector, which was beginning to boom in the 1990s, in Chennai among other Indian cities. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), an Indian software engineering firm, became a key private-sector partner in this process, in part by establishing their own IT campus in a Chennai suburb in 1999. Jayalalithaa aided TCS immensely: a company representative has stated that, “We had to build the roads. We had to buy land from government and private parties. When we had a problem with some clearance, the then Chief Minister Jayalalithaa stepped in and sorted it out.”[_]

The second way in which political commitment to industrial development manifested in Tamil Nadu was through the policy consistency that successive, opposing administrations maintained over time. Though the DMK and AIADMK have frequently swapped places in power, the state’s approach to investment has remained relatively stable and predictable. As certainty in contracts and property rights are critical to attract and retain investors, the fact that neither party has reneged on major investments negotiated by the other since 1989 has significantly strengthened Tamil Nadu’s ability to attract investment.[_]

Policy consistency has been an enduring feature of Tamil Nadu’s politics not despite but because of the political competition and rivalry between the DMK and AIADMK. Neither party could wipe out the other on ideological grounds, since as discussed previously, they shared a range of positions. Their similar viewpoints translated into overlapping constituencies, for whom they had to compete intensely and deliver tangible benefits. In addition, ideological closeness increased the chances that power would alternate between the two parties regularly, as they had little policy basis on which to differentiate themselves from one another. As a result, it was not in the interest of any given administration to reverse successful policies or block investments secured by the previous administration; doing so would likely go against their own ideology and the preferences of their own constituents. In fact, as a senior ex-bureaucrat in Tamil Nadu said, “If one party’s policies worked earlier the newly elected party would have no hesitation in adopting and improving upon it.”[_] This policy stability was a boon to productive industrial sectors, and even lured those investing in technology-intensive businesses despite their longer timelines for learning and pay-offs.

Again, the automotive industry provides an interesting example. A change in the investment climate following an Enron scandal and state elections in Maharashtra in 1995 influenced Hyundai’s decision to locate in Chennai. Before Hyundai’s operations had been established there, Jayalalithaa and her party, the AIADMK, were trounced in state elections in 1996 by the DMK, again headed by Karunanidhi. Yet his administration lived up to previously agreed government commitments, enabling Hyundai to roll out the first car from their operations in Tamil Nadu in September 1998.[_]

Summing up both these points, a former executive vice-chairman at TIDCO cited the strong support from the state government and the coherent ideas of political leaders from the different ruling parties as the most important factor in boosting FDI inflows, stating: “Government support is very important to promote investments. The commitment of the government to creating relevant policies and incentives is necessary. In the system of democracy, the government (ruling party) keeps changing. An election keeps coming and after five years the government changes. But an industrial development plan needs 40 or 50 years, it does not respect this change of governments. A successful government should keep the promises of the previous government in pursuing such investment projects continuously. This is business, not politics [for economic growth]. Both the DMK and the AIADMK governments consider investment projects as significant for the industry, so the successive government[s have] honoured such industrial promises of the previous government[s].”[_]

Competent and effective administration

Tamil Nadu has a reputation for innovative design and effective implementation of its economic and social welfare policies, which has proven instrumental for the state’s development.[_] This has enabled the state government to translate its lofty ideals into tangible progress on industrial development, education and health (while also reducing leakages of public funds). Indeed, Tamil Nadu’s overall governance is ranked as the second most effective among Indian states.[_]

A variety of factors have made Tamil Nadu’s bureaucracy strong. During the tenures of Anna and Karunanidhi as Chief Minister in the 1960s and 1970s, the state government actively sought to recruit from lower-caste groups, many of whom were from rural areas and thus could better understand rural conditions and issues.[_] As the civil service became more representative of the population, it became more attuned to the expectations and aspirations of the state’s main political parties, the DMK and AIADMK. As a result, civil servants could play a bridging role between these aspirations at the political level and the realities at the community level, which proved useful in delivering tangible social benefits to the state’s residents.[_]

Interestingly, the competition between the two main political parties also served as an impetus to drive implementation. Given the depth of the competition between the DMK and AIADMK, bureaucrats were forced to choose which party to support; remaining neutral was not a viable option. Committing to and openly identifying with a particular party meant that, when that party was in power, civil servants faced pressure from party officials to execute their development agenda as effectively as possible. At the same time, both parties had similar agendas across several dimensions—for instance, both sought to encourage industrial investments and develop links with the private sector. Hence, despite political divisions spanning not only electoral politics but also the bureaucracy, bureaucrats of either political leaning continued to implement policy effectively even if their party of choice was not in power; after all, they were unlikely to have major differences of opinion on policy with the party that they opposed.[_]

The establishment of TIDCO and SIPCOT, nodal agencies for industrial development, also positioned the bureaucracy to follow through on the state government’s economic vision. The focused mandate of these agencies, combined with the prioritisation of industrialisation at the political level, made clear the task of bureaucrats in these agencies—to facilitate between investors and the state government—and, in turn, empowered them to play this role effectively.

For example, with the limited but critical mission of acquiring and managing industrial land, SIPCOT has developed, maintained and managed industrial complexes and SEZs in 12 districts across Tamil Nadu. Commenting on SIPCOT’s performance in 2012, a former Finance Minister of the state, said: “I think our state does not need to worry about land acquisition for the next 15 years as we have already acquired enough land for building various industrial complexes.”[_] SIPCOT’s ability to execute this mandate has served as a foundation for the state to attract domestic and foreign investment alike.

Likewise, TIDCO has played a key role in promoting the state for investment and in getting the state government to meet investor requirements in order to secure their investment. For example, Chennai was initially Ford’s last choice, behind two other potential investment destinations in India. In response, the Tamil Nadu Export Promotion and Guidance Bureau, set up in 1992 under the oversight of TIDCO, “put together a highly professional multi-media presentation on the state which left a very favourable initial impression”.[_] In further discussions, Ford raised hundreds of detailed queries for TIDCO to respond to. As the TIDCO chairman at the time put it, “they were so particular. They wanted us to make sure that there was no other industry within twenty kilometres which will create dust pollution because of their ultra-modern paint shop.” In fact, TIDCO and the state government went beyond this: they guaranteed uninterrupted power and water supply, and immediately started work on an international school for the children of Ford’s staff.[_] Today, TIDCO has institutionalised its investment facilitation efforts, by creating a thorough monitoring system to attract investment projects and regular meetings to push forward the implementation of investment policies.[_]

Chapter 5

Like many African countries, Tamil Nadu’s government and political system has been characterised by intense competition between political parties; networks of patronage encompassing politicians, voters and businesses; and political leaders with big personalities and ambitions. What Tamil Nadu’s development experience in the last several decades illustrates is that these characteristics do not have to render a government completely ineffective in promoting inclusive growth. Indeed, the Tamil Nadu state government, like all governments, has had some degrees of freedom to promote development that improves the lives of a wide range of people in the state. Rather than attempting to detail all of the various elements that have contributed to Tamil Nadu’s development story, the focus of this case study has been on the role that political leadership and administrative capability have played. In particular:

Successive chief ministers of Tamil Nadu in the second half of the 20th century, from Anna all the way through to Jayalalithaa, crafted visions for development in the state that aimed to include disadvantaged groups in the economy and society through job-creating investment/industrial development and broad-based social programmes.

These same chief ministers maintained a commitment to industrial investment and development, as well as a consistent policy approach to encourage them—despite alternating power with opposition parties.

Tamil Nadu’s bureaucracy developed capabilities to effectively implement the state’s inclusive development agenda, as the state’s leadership diversified recruitment along socioeconomic lines; set out clear ideological foundations that bureaucrats associated with them could work from; and established nodal agencies to drive industrial development, such as TIDCO and SIPCOT.

The takeaways for many African countries are simple but important. The economic vision should be geared toward the needs and aspirations of society at large, and should be clear to all parts of government, the private sector and citizens. Economic transformation takes time and thus requires policy consistency and sustained commitment spanning changes in political leadership across multiple decades. And implementation of the vision is just as critical as the vision itself, and calls for the bureaucracy to improve its ability to deliver over time—even if the starting point is a handful of specialised agencies that function as “pockets of effectiveness”. Tamil Nadu is still in the middle of its development journey, but its experience thus far underscores how political leadership and state capability can be leveraged in African countries that seek to follow a similar path.